- Morning Brief

- Posts

- The Silent Epidemic Eating Away American Minds

The Silent Epidemic Eating Away American Minds

A sudden, unprecedented change in mental disorders has scientists worried about what it could mean.

(Illustration by The Epoch Times, Shutterstock)

Billy was a bright 10-year-old boy with two Ivy-League-educated parents. He was book smart—got straight A’s in school—but lacked street smarts.

He was also a poor sport. Billy would frequently lie and cheat when playing board games or participating in team activities and have full-blown meltdowns when he lost. His friends, who had been with him since kindergarten, began losing patience. His parents recognized that something had to be done.

So Billy’s parents brought him to Dr. Victoria Dunckley, a pediatric psychiatrist specializing in screen use.

After a four-week “screen fast” prescribed by Dr. Dunckley, which eliminated all TVs, phones, and video games, Billy’s problems miraculously cleared up. His parents were so pleased that they decided to maintain the fast.

Six months passed, and Billy’s friends were no longer avoiding him, and his sportsmanship had improved markedly. Billy decided to run for class president and delivered a speech, something that would have previously terrified him.

Billy is one of Dr. Dunckley’s many patients whose mental and behavioral problems disappeared once they eliminated or significantly reduced screen time.

Excessive use of screens has become an epidemic silently eroding lives with little resistance. Gallup’s 2012 survey found that around 60 percent of young adults admit to spending too much of their time on the internet; in a subsequent survey, 83 percent of smartphone users said they kept their phone near them “almost all the time during their waking hours.”

People that spend a lot of time on screens outside of work are typically enjoying short videos, film and television, social media, or video games. All of these screen-based forms of entertainment offer a similar emotional experience of novelty, discovery, and instant reward. This process is stressful and satisfying at the same time.

The problem is screens can overstimulate our brains, resulting in perpetual stress, also known as the fight-or-flight state. This state taxes the brain and body and makes us prone to meltdowns, depression, and anxiety when even minor changes in the environment occur.

Rising Problem

The initial link between screen time and poor mental health was spotted through generational studies by Jean Twenge, who has a doctorate in psychology and is a professor of psychology at San Diego State University.

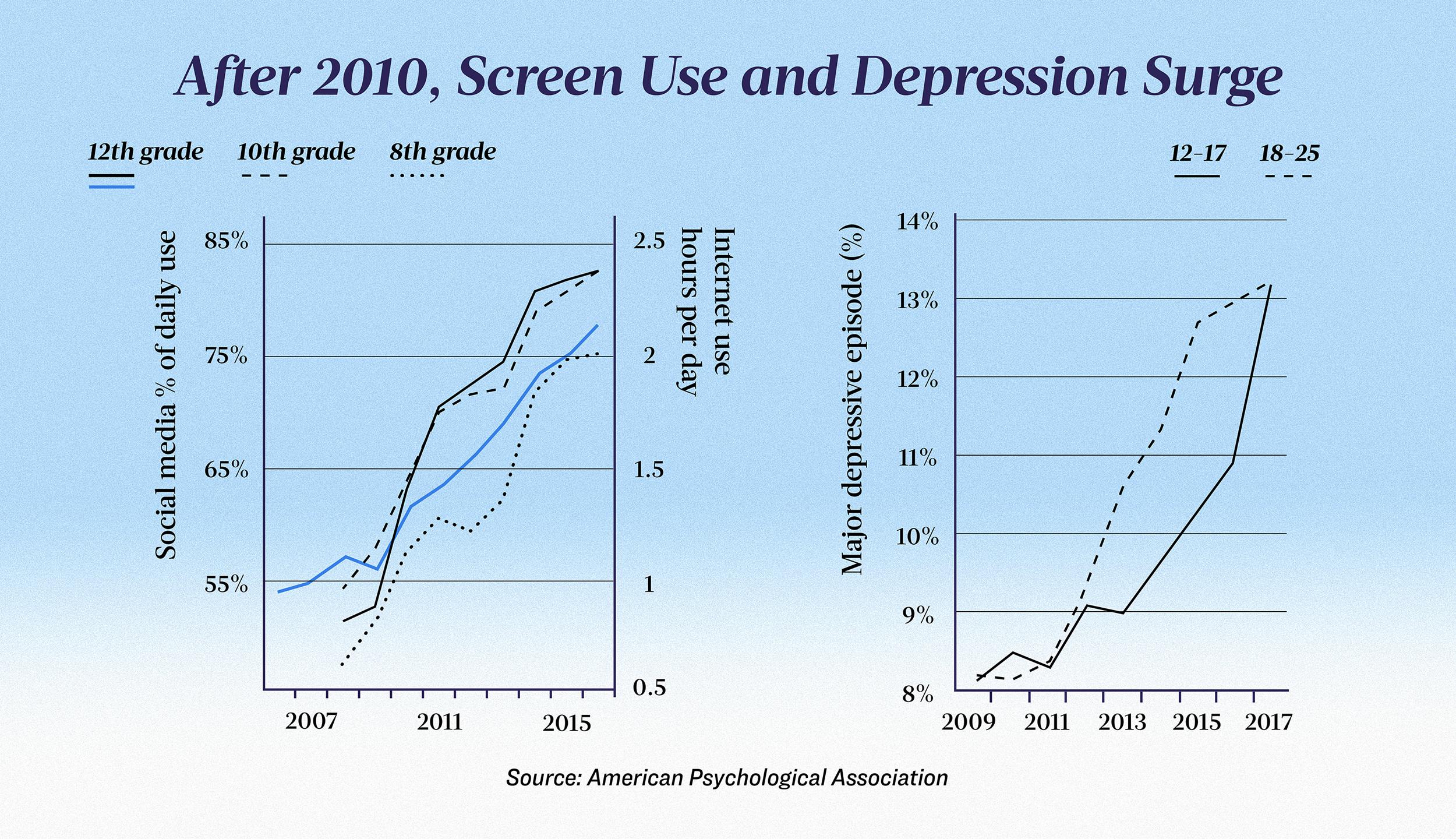

“I got used to changes that would grow slowly and steadily over time,“ but then after 2010, ”I started to see some changes that were much more sudden—I had really never seen anything like it,” Ms. Twenge said in a TEDx talk.

Around 2010, social media and internet use saw a dramatic increase, followed by an increase in major depression. (The Epoch Times)

Between 2005 and 2012, the change in rates of depressive episodes in teens aged 12 to 17 barely exceeded 1 percent. However, between 2012 and 2017, there was an almost 4 percent increase.

Additionally, fewer teenagers are going outside or reading books, while their time on social media and the internet is dramatically surging.

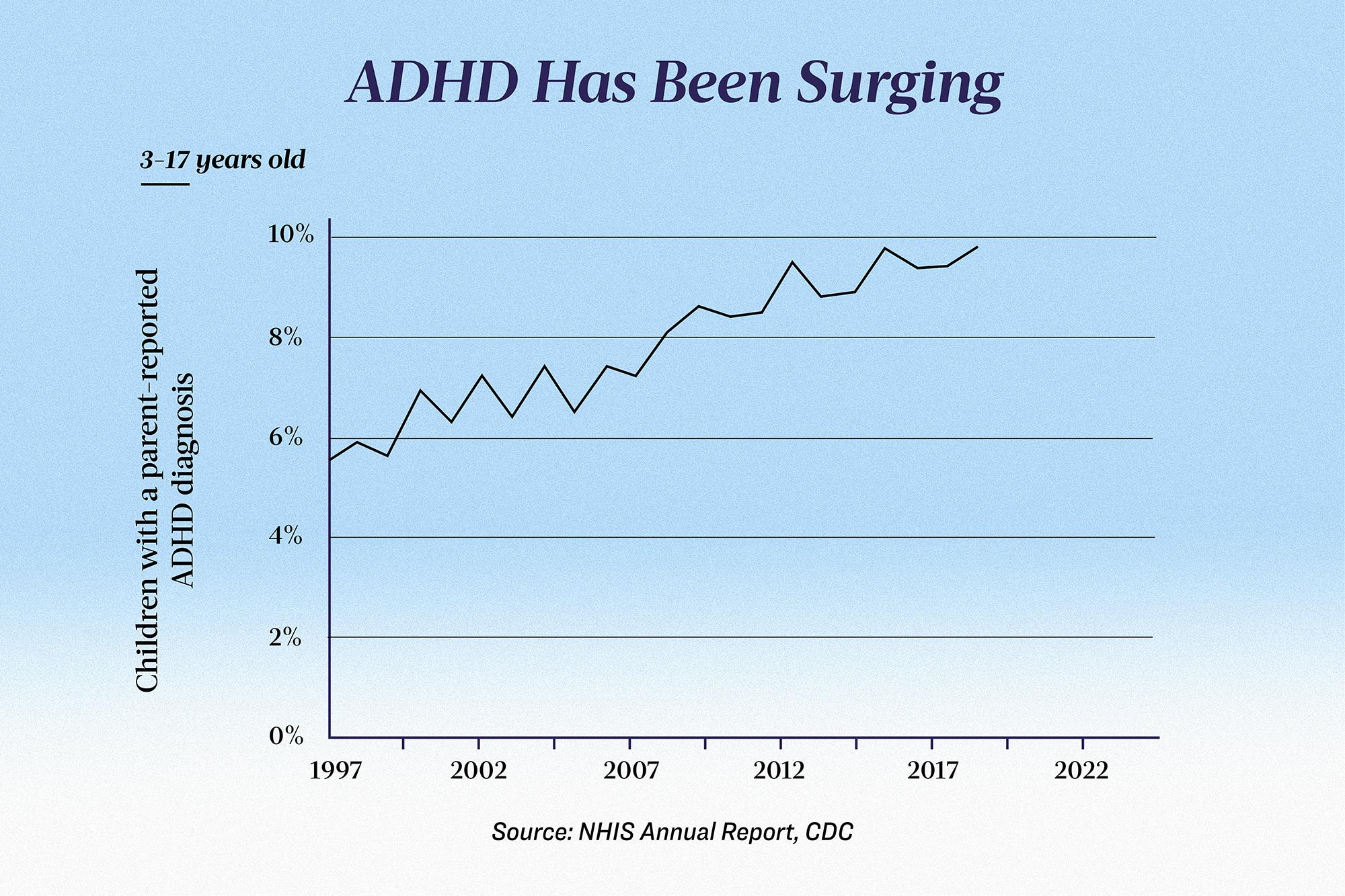

In 2008, psychotherapist Tom Kersting, who worked as a school counselor for 25 years, saw a rise in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) diagnoses in children over age 8.

ADHD tends to be detected in early childhood after a child starts school. However, he has witnessed increasing diagnoses in teenagers and adults. While it could be possible that some of these teens were missed by clinicians when they were young, Mr. Kersting suspects that some developed symptoms of ADHD due to screen use.

ADHD diagnosis has been on the rise. (The Epoch Times)

Around 2012, when 30 percent of teenagers had a smartphone, he started to see rebellious behavior and anxiety disorders becoming more common among children. Young adults and teenagers growing up now also tend to be more antisocial and have reduced emotional resilience, which may be related to insufficient in-person socializing due to spending most of their time behind screens.

“It’s not just the amount of time spent in the cyber world,” Mr. Kersting told The Epoch Times, “but also what they missed out on: outside play and social learning.”

During the pandemic, adolescents’ screen time doubled.

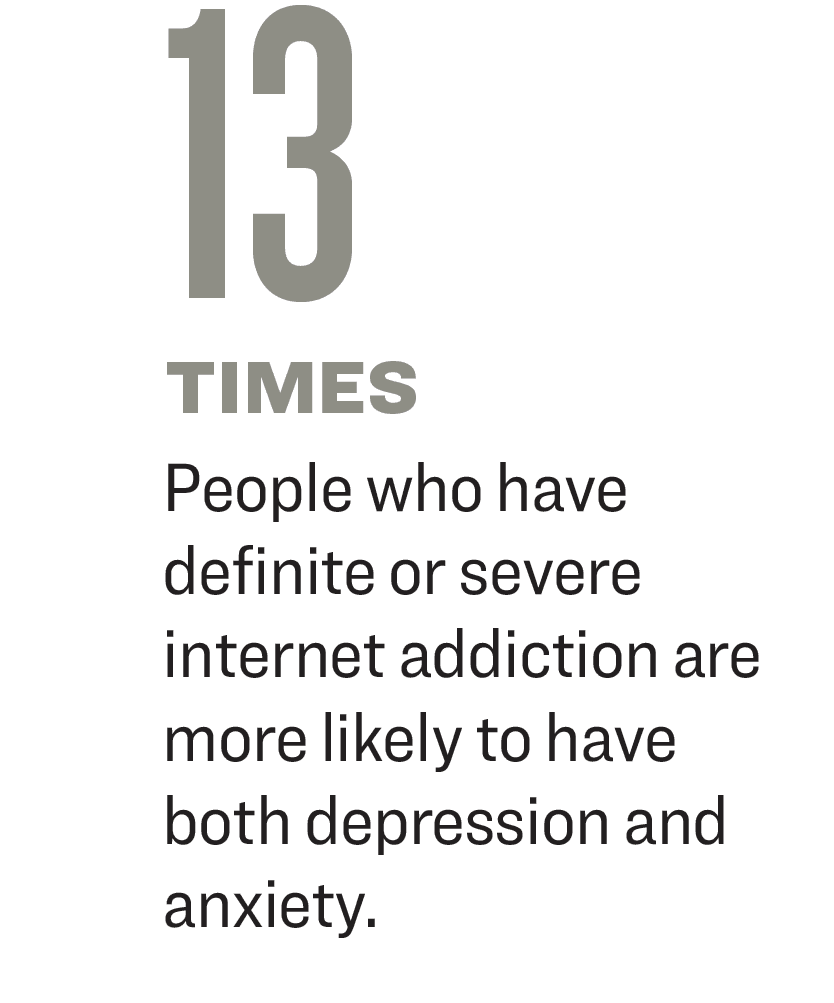

Few studies investigated internet addiction in children during the pandemic, but a large study done in adults in 2021 showed that adults who were considered at risk of internet addiction were 2.3 times more likely to have depression and 1.9 times more likely to have anxiety than the general population. Furthermore, people with definite or severe addiction were 13 times more likely to have both depression and anxiety.

Fast forward to post-pandemic times, with teachers reporting that the latest generation—Gen Alpha, also known as “iPad kids”—is aggressive, undisciplined, and regulates emotions poorly in the classroom.

Dr. Clifford Sussman, a psychiatrist specializing in screen addiction, has focused his practice on treating this condition due to increasing need. Especially after the pandemic, “demand for help with this issue exploded,” he told The Epoch Times.

How Screens Hook You

Screen activities—whether they include video games, social media, internet scrolling, or video streaming—offer an escape. These activities are also highly stimulating for the brain due to their bright colors and seamless integration into the virtual world, medical professor and psychotherapist Dr. David Rosenfeld at Buenos Aires University told The Epoch Times.

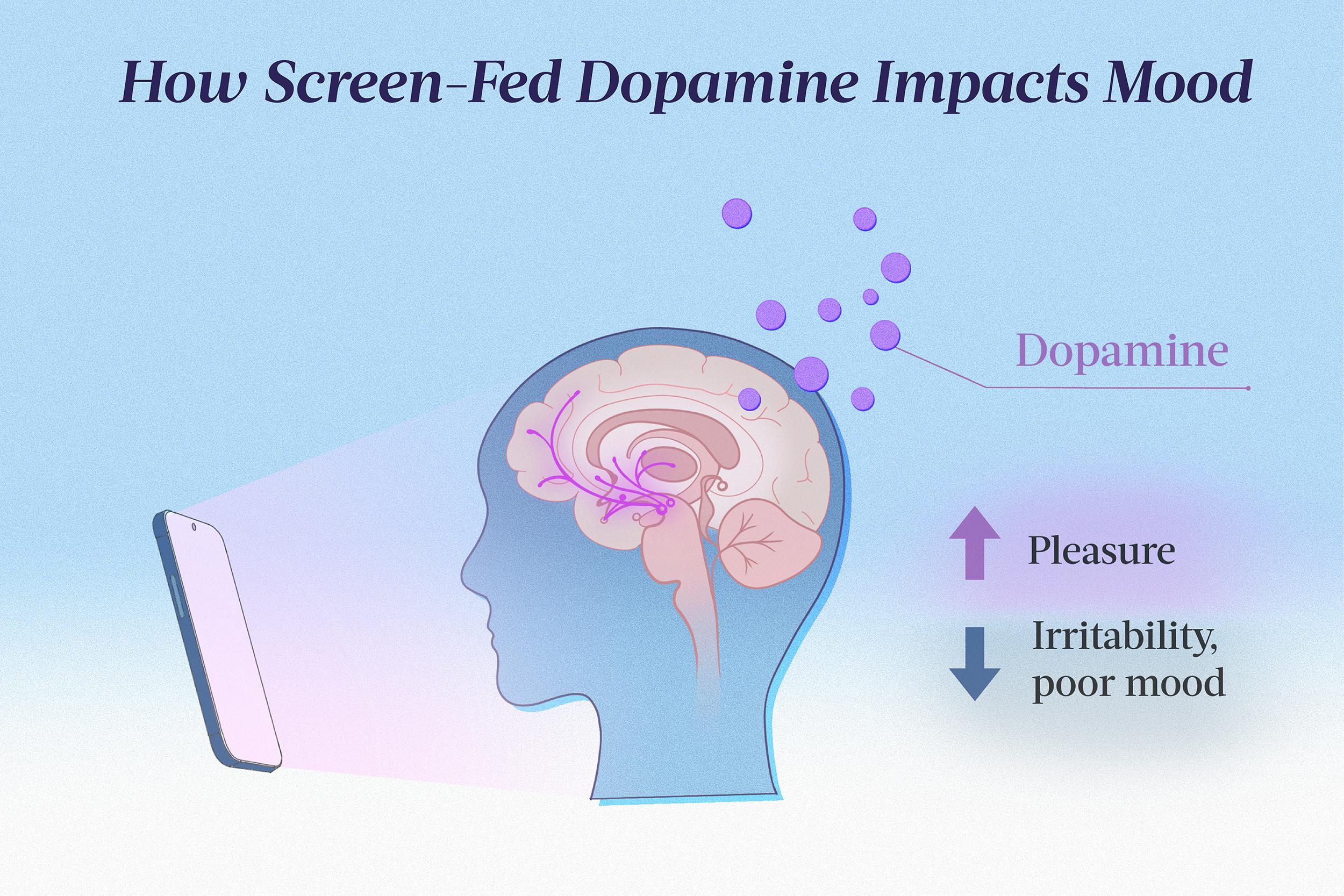

When presented with anything new and exciting, the brain releases dopamine, and anything that induces dopamine release can be addictive. Dopamine produces a feeling of pleasure, while a drop in it is linked to irritability and poor mood.

Dopamine produces a feeling of pleasure, while a drop in it is linked to irritability and poor mood. (Illustration by The Epoch Times, Shutterstock)

Screen activities have been designed to capture our attention by feeding us regular doses of dopamine. Like playing an immersive video game, giving you a thrill when you level up, defeat a boss, or find a new item, screens entice you to spend more time in the virtual world.

“Video games are governed by microscopic rules,” Bennett Foddy, who teaches game design at New York University’s Game Center, said in the book “Irresistible: The Rise of Addictive Technology and the Business of Keeping Us Hooked” by Adam Alter, as excerpted by The Guardian.

These micro-rules can be a “ding” sound or a white flash whenever a character moves over a particular square and are synced to the player’s actions so they feel they were the one who caused it. This micro-feedback generates a sense of reward, hooking people into continuously playing the game.

This system may also explain why interactive screen activities may be more problematic for children than passive screen activities, like watching TV.

Dr. Dunckley has observed that while two hours of TV is linked to signs of dysregulation in children, only 30 minutes of interactive screen activities is stimulating enough for signs to occur.

Many video games also employ strategies used in gambling, such as loot-box rewards, where players are rewarded at random intervals throughout the game. Since players do not know when the next reward drop will come, they are further compelled to play the game—even if they are not enjoying it.

This strategy came from the works of psychologist Burrhus Frederic Skinner. Skinner put pigeons in a box with a button, rewarding them with food whenever they pressed it. He found that the pigeons rewarded irregularly were more compelled to press the button than those rewarded with every button press.

This compulsion also exists in humans.

A child plays video games at a trade fair in Milan, Italy, on Nov. 22, 2013. (Tinxi/Shutterstock)

Social media posts break information into bite-sized pieces, feeding users a jolt of dopamine with every post, like, and comment.

Furthermore, social media has been engineered to lack natural stopping cues inherent in many aspects of life.

Whether it’s a newspaper article, book, or movie, there is always an ending. One is, therefore, left to choose another activity once the end of the article, chapter, or movie comes. However, with social media, one can scroll on forever without an end to the content—known as the doom scroll.

Internet surfing is no different. Put a word into the search engine, and endless results and related links surface, leading you down a rabbit hole.

When Screentime Eats Into ‘Human’ Time

The social acceptability and pervasiveness of screens often make it hard for people to realize that their screen time may be getting out of control.

So far, no consistent criteria on what counts as screen addiction exists, but there are increasing data suggesting that many Americans have problematic screen use.

Americans spend seven hours a day behind screens on average, excluding time spent at school or work.

Counsellor Hilarie Cash, the co-founder of reSTART Life, a residential treatment center for tech addiction, told The Epoch Times that screen use is classified as problematic when it starts eating into time necessary for normal human functioning.

People need around eight hours of sleep every day, and the average working time is 8.5 hours. They also need time to socialize, exercise, eat, shower, and manage daily affairs and hobbies. Seven hours of screen time daily would mean necessary activities are being sacrificed.

Dino Ambrosi, the founder of a 12-week program that helps college students limit social media time, estimated in a TEDx talk that if most 18-year-olds today lived to be 90, they would have 334 months of free time left in their lives.

What those people do with this remaining time “will quite literally determine the kind of person you become,” he said. Yet Mr. Ambrosi’s estimations show that around 93 percent of that time is spent behind screens—mostly unintentionally.

Ms. Cash, whose program to treat people struggling with addiction to internet pornography and video games began in the 1990s, has observed a worrying trend.

While her earlier clients also experienced major upheaval due to their screen addictions, they had sufficient life skills. In contrast, many of her clients today lack necessary life skills, such as knowing how to cook, maintain personal hygiene, hold down a conversation, make meaningful relationships, keep a job, etc. These people are more challenging to treat.

One reason for this is that they were given a tool to escape early into their childhood or adolescence. As a result, they have become chronic escapers of inconveniences and difficulties in life. Ms. Cash said these people struggle to build social connections, navigate challenges, and hold down a job—all essential in helping a person construct a life outside the virtual world.

4 Major Mental Disorders

Psychologists and professors Daria Kuss and Mark Griffiths at Nottingham Trent University are some of the leading researchers investigating the effects of problematic screen use.

Among the 26 psychotherapists who treat people with internet addiction who Ms. Kuss and Mr. Griffiths surveyed, some said their patients’ mental health problems were undoubtedly caused by screen use.

“They didn’t have social anxiety or generalized anxiety disorder prior to when they started playing,” one psychotherapist reported.

Dr. Sussman added that when comorbid with addiction, mental health problems are often untreatable before first addressing the addiction.

Depression

Prolonged screen entertainment leads to protracted periods of dopamine release. This means one experiences a dopamine drop when quitting screen time. Low dopamine levels are linked with irritable mood and depression.

With constant stimulation, the body eventually attempts to stabilize itself by making the brain’s pleasure pathways less sensitive. This means that to achieve the same “high,” a person must either increase how stimulating the content is or watch more. This could mean more graphic, intense, or violent content. Then, when a person gets off the screen, this results in further disinterest and poor mood.

Naturally, people are less interested in less-stimulating activities—like inherent, interpersonal pleasures.

Screen use is also associated with low melatonin release, which can disrupt sleep and is potentially linked to a variety of mood disorders, including depression.

Since 2010, fewer teenagers go out with their parents, and the percentage of children reporting depression symptoms has surged. (Alain Jocard/AFP via Getty Images)

Anxiety and Irritability

Being on the screen means a person is constantly distracted.

Social media and internet scrolling break up a person’s attention span, as attention is diverted from one thing to the next. “We find in our research a correlation between frequency of attention switching and stress,” researcher Gloria Mark, who has a doctorate in psychology, said in an interview on the podcast “Speaking of Psychology.” The faster the attention switching occurs, the higher the stress—measured by heart rate monitors and self-reporting.

Stimulation from screens also activates the fight-or-flight response and causes adrenaline to be released. This adrenaline rush can cause a sense of anxiety or great excitement. If this state continues to be triggered, a person may become adrenaline-depleted, said pediatric occupational therapist Cris Rowan, a critic of the impact of technology on human development, behavior, and productivity. Adrenaline depletion can lead the body to release cortisol instead, Ms. Rowan said. Cortisol is a stress hormone linked with anxiety and major depressive disorders.

ADHD

A major disorder linked with screen misuse is ADHD.

The brain is like a muscle that can be trained, said Dr. Andrew Doan, an ophthalmologist specializing in public health, problematic gaming, and excessive personal technology use.

Since screen entertainment is highly distracting, time on screens comes at the expense of time used to train a person’s ability to sustain attention, which is required to complete a mentally challenging task like finishing lengthy homework.

Prolonged screen time is also associated with thinning of the prefrontal cortex, which is critical for compulsion control and logical thinking. This is also what makes people with ADHD have difficulty in completing tasks they find uninteresting.

Autism

Screen time is isolating.

While a person is engaging with games, social media, and the internet, “the question is, what are they not doing?” Mr. Kersting asked.

For parents, this might be parenting and building a connection with their children. For children, it could be opportunities to play and socialize, which stunts social development and can lead to withdrawn, antisocial, and anxious behaviors that can mimic symptoms of autism.

Drs. Dunckley and Sussman have discussed that the formation of problematic screen usage and mental health problems can be bidirectional. In other words, people with autism or autism-like symptoms may use screens to avoid socially anxious situations, but the less they train themselves to be social, the more withdrawn they become.

Avoiding Screens Is Like ‘Drinking Water in a Bar’

Problematic screen use is not limited to children. Ms. Rowan, who has conducted over 400 workshops on topics such as productivity, addictions, technology overuse, media literacy programs, and school environmental design, said that parents sometimes enable children to seek out screens.

“Raise your hand if you’re managing your screen use adequately,” Ms. Rowan asked a room of adults during one of her workshops. While about 500 people signed up for it, fewer than 10 people raised their hands.

The work of educator and clinical psychologist Catherine Steiner-Adair has also shown that children are increasingly competing with screens for their parents’ attention. Some children have reported feeling neglected because their parents are constantly checking their phones.

Parents who are unaware or not in control of their own screen use may also struggle to set screen time limits for their kids.

Some parents are now raising their children by using screens as babysitters. This can cause children to prioritize screens over family and vice versa with the parents, Dr. Rosenfeld said.

This phenomenon is reflected in Gen Alpha. A common issue with these children is a lack of discipline, leaving parents stressed, and only screens can pacify them during their tantrums.

Schools and workplaces going digital have also facilitated screen use.

As entertainment is often a click away, Dr. Sussman described the difficulty of cutting screen use in the current environment: “It’s like drinking water in a bar.”

When asked if people can recover from an addiction, Dr. Rosenfeld said that the most crucial factor is having a loving family that cares and is willing to do everything to help the person get better.

But what about the new family dynamic where parents are also addicted to their screens and, therefore, do not see their children’s screen addictions as much of a problem?

“That is not a situation a psychoanalyst can help with,” Dr. Rosenfeld said somberly.